(A Nervous System Doing Its Job)

There is a particular kind of moment in therapy that can catch even experienced counsellors off guard.

A client reacts strongly – suddenly, intensely, and in a way that feels disproportionate to what’s just happened.

A raised voice.

Tears that arrive without warning.

A sharp withdrawal.

A look of panic, shame, or anger that seems to come out of nowhere.

And inside the therapist, a quiet alarm may sound.

What just happened?

Did I say something wrong?

Why does this feel so big?

It’s often at these moments that clients are described – sometimes gently, sometimes not – as overreacting.

Attachment-informed work invites us to pause right there. Because from the perspective of the nervous system, there is no such thing as an overreaction.

There is only a reaction that makes sense in the context of what the body believes is happening.

When intensity isn’t about the present moment

One of the most disorientating aspects of working with trauma and attachment is that the nervous system does not operate in linear time.

When a client reacts intensely, they are not responding solely to now. They are responding to a moment that feels familiar – even if neither of you can immediately name why.

A tone of voice.

A facial expression.

A perceived withdrawal.

A question that lands too close to something vulnerable.

For a nervous system shaped by early relational threat, these cues can signal danger long before the thinking brain has a chance to intervene.

So what looks like an overreaction in the present is often a perfectly proportionate reaction to the past.

The body is not confused.

It is remembering.

Survival states masquerading as personality traits

Clients who are described as “too emotional”, “volatile”, “dramatic”, or “highly sensitive” are often living in nervous systems that learned early on that threat could arrive suddenly and without warning.

Their responses are fast because they had to be.

Fight, flight, freeze, or collapse are not character flaws – they are survival states. And once established, they don’t simply switch off because circumstances improve.

In therapy, these states can show up as:

- Anger that flares quickly

- Tears that feel unstoppable

- Sudden shutdown or dissociation

- A desperate need for reassurance

- A sharp rupture over something that feels minor

Seen through a behavioural lens alone, these reactions can feel confusing or even manipulative.

Seen through a nervous system lens, they are deeply coherent.

What happens inside the therapist

Intensity doesn’t just affect clients – it affects therapists too.

When a client reacts strongly, therapists often experience:

- A surge of responsibility

- Anxiety about making things worse

- A pull to soothe, explain, or fix

- A desire to retreat, contain, or regain control

These responses are human. They’re also relational.

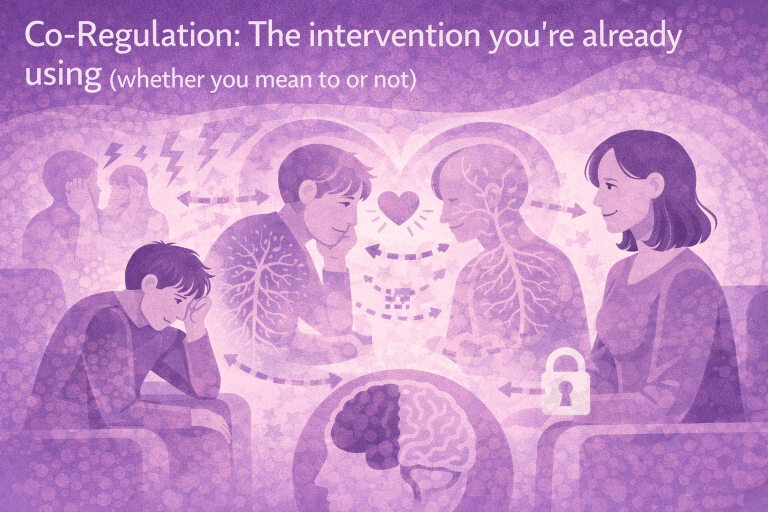

Attachment-informed work invites us to include our own nervous system in the picture, rather than trying to rise above it.

If you feel overwhelmed, pulled, or destabilised, it’s often because the client’s nervous system is communicating at a level below words.

This isn’t something to correct – it’s something to orient to.

Regulation before meaning

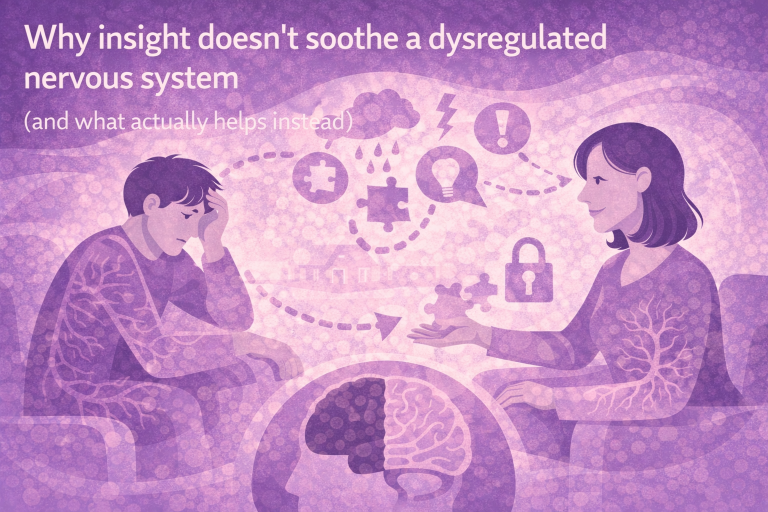

One of the most common missteps in moments of intensity is trying to make sense of what’s happening too quickly.

We ask questions.

We explore meaning.

We offer interpretations.

But when a client is in a heightened survival state, their capacity for reflection is limited. The brain regions responsible for insight and narrative are simply not online.

In those moments, the most therapeutic intervention is often not cognitive at all.

It’s regulation.

This might look like:

- Slowing your pace

- Softening your voice

- Naming what you notice without analysis

- Offering grounding through breath or sensation

- Reducing demands rather than increasing them

These are not techniques layered on top of therapy – they are therapy, when working with attachment and developmental trauma.

Making sense without minimising

There’s an important distinction here.

Understanding that a reaction is nervous-system driven does not mean excusing harmful behaviour, abandoning boundaries, or colluding with patterns that cause damage.

It means we stop shaming the response – internally or externally – and start working with it intelligently.

Instead of:

“This feels out of proportion.”

We might gently wonder:

- What does this response believe it’s protecting against?

- How old might this part of the client be?

- What feels at risk right now?

These questions don’t need to be spoken aloud. Often, holding them internally is enough to change the tone of the session.

When clients fear their own reactions

Many clients who “overreact” are deeply ashamed of their intensity.

They apologise.

They minimise.

They fear being “too much”.

They worry the therapist will reject them.

For these clients, the therapy room can feel like a test:

Will this reaction finally be the one that’s too much?

How we respond in these moments matters enormously.

Not by normalising everything, but by staying present, grounded, and curious – signalling through our nervous system that intensity does not equal danger here.

This is often how safety is built: not in calm moments, but in how intensity is held.

A different way of measuring safety

In attachment-focused work, safety is not the absence of strong emotion.

Safety is the ability to move through emotion without losing connection.

When a client learns – slowly, experientially – that their reactions can be met without panic, judgement, or withdrawal, something begins to shift.

The nervous system updates.

Not because it was told to – but because it experienced something different.

A reflection to take into your work

The next time a client’s reaction feels “too much”, you might pause and ask yourself:

- What might this nervous system be responding to?

- What does my own body feel right now?

- What would help create a little more safety in this moment?

Often, the most powerful thing we can offer is not an explanation, but a regulated presence that says:

I can stay with this.

You don’t have to manage it alone.

In the next blog, we’ll explore what gets missed when we stay focused only on the present – and why thinking developmentally can transform how we understand stuckness, repetition, and emotional intensity.

For now, you might simply notice this:

Which client reactions have you been secretly labelling as “overreactions” – and what might change if you saw them instead as a nervous system doing its job?

Sometimes, that shift is where compassion – and clinical clarity – quietly begins.