(Even When the Client Is 58)

At some point in attachment-informed practice, many counsellors have a quiet realisation.

The client sitting in front of us may be an adult – articulate, capable, reflective – and yet something else is present too.

A fear that feels too big.

A longing that feels strangely young.

A reaction that seems to bypass logic altogether.

It’s often here that inner child work begins to edge into the therapeutic picture – sometimes welcomed, sometimes met with uncertainty.

And yet, from a developmental perspective, this isn’t an addition to therapy.

It’s an acknowledgement of what has always been there.

Because in attachment-focused work, there is always a child in the room – even when the client is 58.

Inner child work isn’t symbolic – it’s developmental

The phrase inner child can provoke mixed reactions. For some, it evokes depth and compassion. For others, it feels vague, regressive, or worryingly unboundaried.

But clinically, inner child work is not metaphorical or indulgent.

It is a way of working with developmentally organised emotional memory.

Early attachment experiences are not stored as stories with beginnings and endings. They are stored as sensations, expectations, impulses, and relational templates.

When those experiences were painful, confusing, or overwhelming, parts of the self can remain organised around the needs and fears of that time.

These parts don’t disappear with age.

They surface when:

- Clients feel misunderstood

- Needs aren’t met

- Boundaries are introduced

- Relationships feel uncertain

And crucially, they surface in the therapy room.

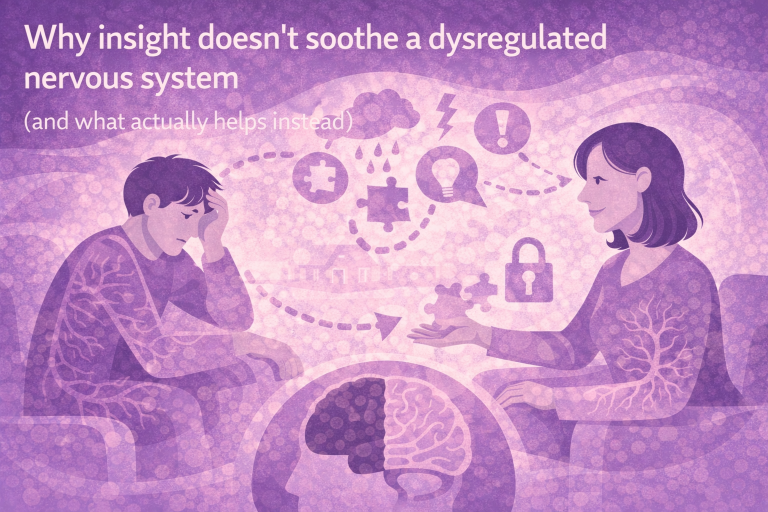

The adult story and the child experience

Many clients can speak fluently about their childhoods.

They understand what happened.

They can make sense of the family dynamics.

They’ve often done years of reflective work.

And yet – emotionally – they remain caught.

This is because knowing about childhood is not the same as working with the parts of the self that were shaped within it.

The adult narrative may say:

“I know my parents did the best they could.”

The child part may still feel:

“I was alone.”

“I didn’t matter.”

“I had to manage on my own.”

When therapy addresses only the adult narrative, the child experience remains unspoken – and unchanged.

How the inner child shows up in the room

Inner child material rarely announces itself clearly.

It arrives sideways.

Through:

- Sudden emotional flooding

- Shame that feels disproportionate

- A desperate need for reassurance

- Withdrawal after closeness

- Fear of disappointing the therapist

These moments are not signs that therapy is going wrong.

They are signs that something important is happening.

A younger part of the client is making contact – often tentatively, often fearfully – testing whether this relationship might be different from earlier ones.

Why inner child work requires safety, not speed

One of the most common mistakes in inner child work is moving too quickly.

Naming the child part.

Asking questions.

Inviting dialogue.

For clients whose early needs were unmet or unsafe to express, this can feel exposing rather than supportive.

Attachment-informed inner child work is slow by design.

It prioritises:

- Regulation before exploration

- Relationship before technique

- Presence before interpretation

Often, the most important work happens not through what is said, but through what is experienced – the therapist staying grounded, attuned, and emotionally available when the child part emerges.

What this asks of the therapist

Working with inner child material brings therapists face-to-face with dependency, vulnerability, and unmet need.

This can stir our own attachment histories – our comfort with closeness, our fears of being pulled into rescue, our beliefs about professionalism and boundaries.

Attachment-focused training places as much emphasis on the therapist’s internal world as the client’s – because inner child work done well requires clarity, containment, and self-awareness.

Not every impulse to soothe is attunement.

Not every boundary is rejection.

Learning to tell the difference matters.

When the child is finally met

For many clients, inner child work isn’t about revisiting the past.

It’s about finally being met in the present.

When a younger part of the self experiences:

- Being taken seriously

- Being responded to with steadiness

- Having needs named without being overwhelmed

Something shifts.

Not dramatically.

Not quickly.

But developmentally.

The nervous system updates its expectations.

The adult self gains more space.

The old strategies soften their grip.

This is not regression.

It is growth that was interrupted – quietly resuming.

A reflection to carry with you

You might reflect on this in your own work:

- Which clients become “younger” at certain moments?

- How do you respond internally when vulnerability increases?

- What helps you stay grounded when dependency emerges?

In attachment-informed therapy, inner child work is not a specialism.

It is simply what happens when we take development seriously.

In the next blog, we’ll explore what therapists sometimes mean when they say “I don’t do inner child work” – and what that stance might be protecting, both clinically and personally.

For now, you might gently hold this question:

If there is always a child in the room, what helps you stay present when that child finally feels brave enough to show up?

Often, that’s where the deepest work begins.