We are, at our core, relational beings.

Wired for Connection: Attachment, Loneliness, and Love in the Age of AI

We are, at our core, relational beings.

From our first breath, we are wired to seek safety, comfort, and meaning through connection with others. Attachment is not a luxury of childhood — it is the survival force that shapes how we love, how we trust, and how we belong.

And yet, as we move deeper into the digital age, our relationships are increasingly mediated through screens, apps, and algorithms. We are witnessing a cultural shift in how people form, sustain, and even replace relationships — not necessarily with other humans, but with digital companions designed to mimic them.

As an attachment-focused psychotherapist, I find this both fascinating and deeply concerning.

The Promise of Digital Connection

Technology has transformed the way we relate. For some, digital connection has been life-saving — allowing contact for those who are isolated, disabled, or geographically distant. The online world can provide community, affirmation, and even the courage to reach out for help.

However, we’re now stepping into more complex territory. We no longer use technology to communicate; we’re beginning to use it to connect emotionally — even romantically.

Artificially intelligent chatbots and “AI companions” promise unconditional presence (whilst you have an internet connection!) and acceptance. They mirror our tone, echo our moods, and respond with warmth and empathy. They offer a form of relationship without risk — intimacy without vulnerability.

And therein lies the danger.

Attachment and the Allure of Safety

Attachment theory teaches us that our earliest caregivers form the blueprint for how we relate throughout life.

If we experienced care as predictable and responsive, we’re likely to expect that relationships can be safe and secure.

But if care was inconsistent or rejecting, we may learn that closeness is risky, that love must be earned, or that it’s safer not to depend on anyone at all.

AI companions appeal precisely because they bypass those risks. They are endlessly available, never critical, and perfectly attuned — a digital version of the fantasy parent or ideal partner.

For those with anxious attachment, this constant availability soothes the fear of abandonment.

For those with avoidant attachment, the lack of demand feels wonderfully safe — connection on their own terms, without exposure.

It’s easy to see the pull. The relationship feels regulated, reliable, safe.

But it is also utterly one-sided.

Pseudo-Intimacy and the Loss of Real Relationship

In Love in a Digital Age, Linda Cundy writes about how technology can offer “pseudo-intimacy” — relationships that simulate closeness without requiring genuine emotional exchange.

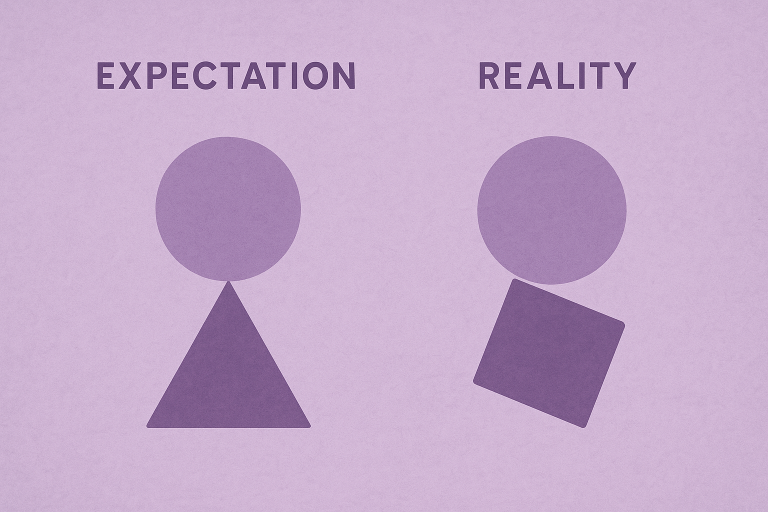

In these digital relationships, there is no true “other” — no unpredictable mind or heart to meet. Instead, we are engaging with a reflection of ourselves, a carefully programmed echo that never interrupts or disagrees.

Linda argues that while such relationships can soothe loneliness in the short term, they risk weakening our tolerance for the reality of human relating. Real relationships involve difference — two people with separate thoughts, moods, histories, and desires. That difference can be uncomfortable, but it is also what creates depth, empathy, and growth.

When every digital interaction affirms us, we lose the developmental tension that allows genuine intimacy to form. We may feel connected, but it’s a connection without friction — and therefore without authenticity.

Why We Need the Mess

True attachment relationships are messy.

They involve rupture and repair — moments of disappointment, misunderstanding, and reconnection. It’s through these cycles that we learn trust and resilience. When a caregiver misreads us and then returns to repair, our nervous system learns that the world is safe enough to risk vulnerability again.

AI companions can simulate empathy, but they cannot misattune — and therefore cannot repair. They can echo compassion, but they cannot offer genuine accountability or remorse.

Without the experience of rupture and repair, there is no opportunity for growth. We remain in a relational echo chamber — safe but stagnant, mirrored but never met.

Loneliness and the Search for Safety

Loneliness is a form of relational hunger. It’s not simply the absence of company but the absence of attunement — of feeling known, understood, and emotionally held.

Linda reminds us that digital connection can temporarily soothe that ache but cannot replace embodied, reciprocal contact. The glow of the screen is no substitute for the warmth of another person’s presence.

When loneliness becomes chronic, our attachment system becomes overactive, scanning for connection wherever it may appear — even in artificial forms. AI companions offer immediate gratification, but they don’t provide the nourishment our nervous systems require.

They are the emotional equivalent of fast food: quick comfort, no real sustenance.

The Cost of Perfection

Real human connection requires us to tolerate imperfection — in ourselves and others.

The fantasy of the flawless, ever-attuned companion removes this vital ingredient. When our digital “partner” is programmed to please, we never have to face the discomfort of being misunderstood, the humility of apologising, or the courage of forgiving.

In therapy, we know that those moments of discomfort are where healing happens. It’s in the missteps and repairs that clients learn that connection can survive imperfection.

If technology gives us only smoothness and ease, it deprives us of the friction that forms emotional maturity.

Attachment Needs in a Disconnected World

Our growing reliance on digital interaction reveals a collective attachment dilemma. We crave connection but fear the vulnerability it demands.

The digital world promises us the illusion of intimacy without the labour of relating. But what it offers instead is contact without connection.

From an attachment perspective, this leaves our deepest needs unmet:

- The need to be seen by a responsive other, not an algorithm.

- The need to co-regulate — to feel calm in another’s presence.

- The need to experience repair after rupture.

In her book, Linda warns that when we replace embodied relating with virtual connection, we risk losing these essential human experiences. The more we retreat into digital safety, the more intolerant we may become of the unpredictability of real love.

Towards Real Connection

The challenge for us — as therapists and as humans — is not to reject technology but to stay awake to what it offers and what it cannot give.

We can be grateful for digital tools that support communication, while holding firm to the truth that attachment requires embodiment.

As therapists, we can:

- Help clients explore what their digital relationships meet — and what they avoid.

- Support reflection on the difference between feeling connected and being connected.

- Model the qualities of presence, imperfection, and repair that no software can simulate.

- Encourage community, shared spaces, and the rediscovery of face-to-face contact.

Because while technology can mimic attention, it cannot attune. It can recognise words but not emotion, process speech but not silence, and respond — but never relate.

A Human Ending

We are, as Bowlby taught us, wired for connection. And as Linda Cundy reminds us, love in a digital age still depends on the same ingredients it always has: mutuality, presence, vulnerability, and repair.

AI may offer comfort, but only a human relationship can offer belonging.

In the end, what keeps us grounded is not the device in our hand, but the heartbeat of another person nearby.

Because it’s in the mess — the misunderstandings, the laughter, the shared silences — that we truly remember who we are: relational beings, beautifully imperfect, endlessly seeking connection.

If you are interested in bringing Attachment into your therapeutic practice, you might like to check out our CPCAB Level 5 Diploma in Attachment Psychotherapeutic Counselling Diploma 😊